The painting never dies

The exhibition that the MEAM is presenting this September, 2016, is perhaps one of the most ambitious ever done by a museum around the figure of a sole author. Close on 200 largeformat items brought together in the Foundation's warehouse, of which, due to lack of morc natural space, some 140 are exhib-ited in the three floors of Palau Gomis, giving an approximat idea of an initiative that only aims to return the artist to his public. An artist that quite a few painters from all over the world follow and admire but who, for diverse circumstances that we analyse here, the majority of people had forgotten about until now.

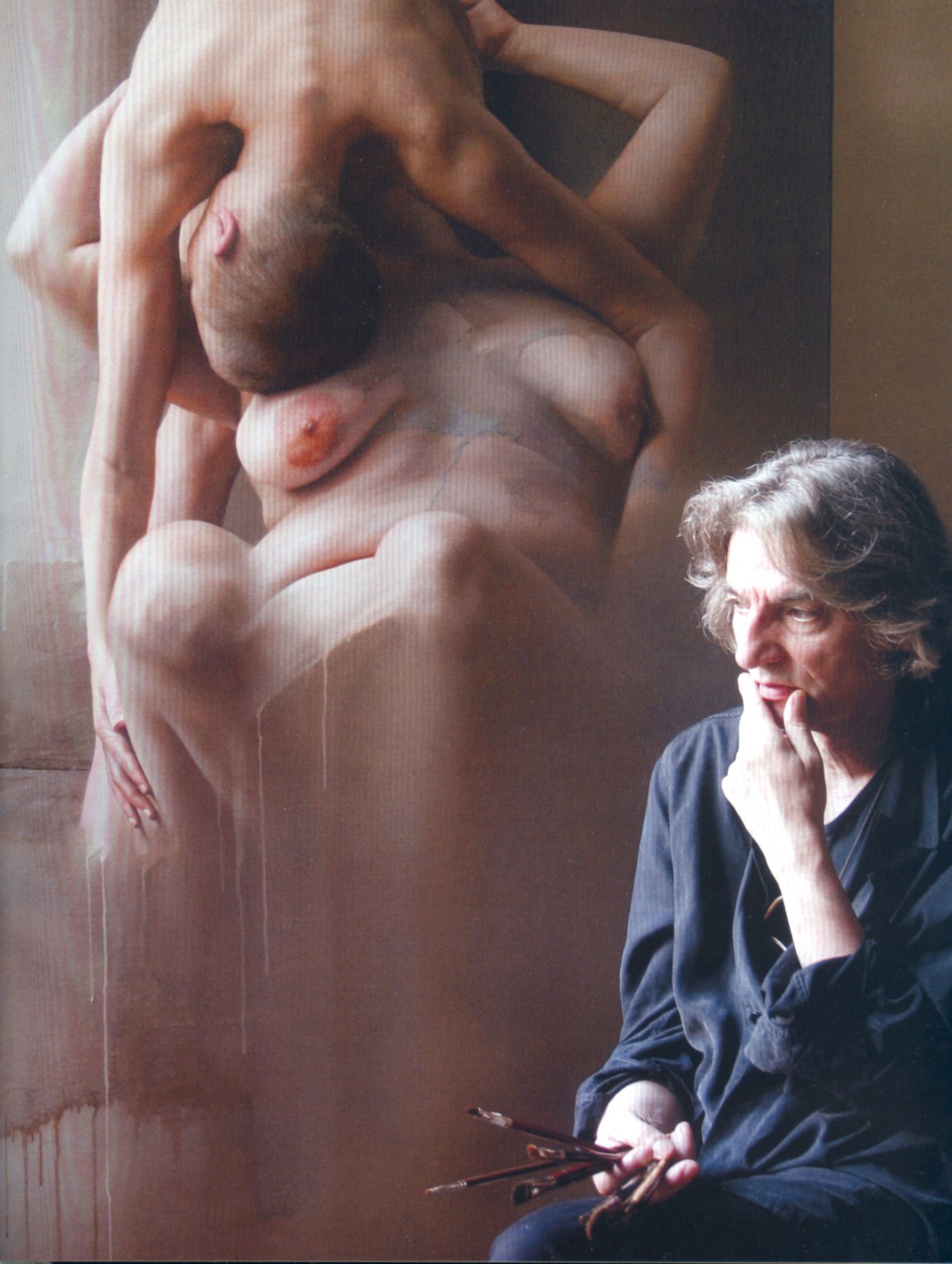

Sandorfi's work is of an extraordinary expressive strength, a visceral, primitive strength, born from within due to authentic necessity. Gifted with a powerful and brilliant personality, he was always clear about what he wanted to do and how he wanted to do it. «Painting is also, and above all, a spiritual need».

Strongly individualist, a sole protagonist in his own world, voluntarily independent of any inkling of external influence, he found in himself, in his own physique, in his face and his body, asin that of his partner and daughters, the excuse to paint, the material object over which to spew out all his flow of expressiveness, painting without any order, without discipline, but also without stopping, without measure, without control ... «and, above all, the freedom to paint at any time, day or night, alone, without the presence of models,

and without any conditioning of light». It would not be until much later, in the final stage of his life, when he would forget this monogamic subject matter to go on and entertain himself with the female body, of the model in the studio, among blankets and sheets ... «Since 1987, I no longer use anything other than female models. « Use» is the right word, since I don't paint the women, but rather I use them to give a presence to my paintings. This means I have to produce a sweeter, more correct painting, of a retained, less apparent and therefore more implicit aggressiveness. I cannot break up a woman. I love painting black women because of the bluish reflection of their skin, but it is never about a contemplative choice. For me the model is a pretext, some «raw material» that serves as a support for the organisation of a closed universe.»

Born in Budapest on the 12 June 1948, at a very early age he had the awareness of solitude before the world, and this solitude, intimate solitude, would accompany him until his death. Forced to emigrate ín 1956, before the advance of the Soviet tanks, he crossed the Austrian border on foot with his family, reaching a refugee carnp from which shortly after they were able to cross into Germany, where he lived for a couple of years, until finally the chance came of emigrating to Paris, the city in which he would settle until the end of his life.

There is no doubt that this adventure must have had a big impact on a boy who, in his innocence, made the following reflection: «At home, everyone said that communisrn was hell. But at school they taught us that Stalin was Father Christmas. Since then, I have stopped believing in adults».

This critical vision of the world of his elders, as i fit were a world outside of hirn, as if he felt on the outside of this world, is what led hirn to an intirnate conviction of solitude in the rnidst of a setting in which he undoubtedly felt was the only reality that did not produce any mental conflict in hirn. The boy created his own protective casing, to resist the absurd contradictions that reached hím from the outside, and this covering protected for life. «ln the Lyceurn, I spent my tirne drawing solitary ink characters caught in the whirlwind of a conflict that did not concern thern, but of which they were hostages».

This later reflection is of importance if we want to understand the process through which the child becarne an adult incorporating all these ways of thinking: «I rernember the entrance of the Russian tanks in Budapest throughout the night ... They fired their cannons over some barricades... I drew the cannons and the revolutionaries who fired at the Russians. A child has to express the passing of events translating them into a personal expression, and this was my way of doing so. Since then, I never stopped drawing again. Here is where everything started.»

This rejection of the adult world, which they irnposed on hím and he didn't understand, would be a constant in his life, as if he were a big child. «At school, I took refuge in drawing ín order not to have to listen to the teachers». And that is how painting would never be a trade for hím, but a weapon of resistance, a vital need, a tool that would enable him to survive in a hostile world. «It's not that l wanted to be a painter one day, it happened on its own».

Questioned rnuch later about which school could his style be assirnilated into, he replied with conviction: «ln the school where they can't stand the school or schools. l do an individualist painting, solitary, which portrays rny way of being, because it springs naturally from rne, and l don't have to rnake any effort to adapt, or to align myself with the latest tendencies. ln reality, l do lazy painting before the conditionings of cultural gregariousness. l don't take any notice of other people's painting, in any case, naturally, they do not to inspire me. I don't have the least interest in classifications that try to place artists in compartments or, rather, in coffins, to bury thern in a cernetery of references, so that people get the impression that this way they know the history of painting.

Painting is not a question of knowledge, but of sensitivity, and this is not taught but learnt. They have tried to classify me among the hyperrealists, among the neo-surrealists, in the new figuration, among the «pompiers», among the fantasy painters (how horrible!) and, rnore accurately, ín the classification of the non-classifiable.»

Already from an early age, the young Sandorfi felt the obsession of the power to perpetuate himself, and he couldn't stand it. He was a rebel from the beginning: «The way they try and impart knowledge ín schools is very humiliating. Above all they teach you to obey, and not reason spontaneously, to memorise without understanding and never answer back. They prepare you to be slaves. And I always had the feeling that they wanted to force my own way of seeing things». And faced with this hostile world, a single refuge: painting. Between the age of fourteen and eighteen, he visited all the exhibitions of Paris, always on his own; he bought painting and drawing books, always drawing. It was ín 1966 when he exhibíted his first drawings in the «Galerie des Jeunes», the first result of this desert crossing that had been and would be his whole life. His father made hím enrol ín the «Ecole des Beaux-Arts», but he knew he wasn't going to learn anything there, and preferred to enrol in the «Ecole <les Arts Decoratifs», simply because here the girls were prettier.

A restless and non-conformist attitude, uncomfortable with society and even with himself, ina fertile, fruitful discomfort, always generating new sen-sations, new visions, passionately experienced, and from which came his first unclassifiable, unassumable, unadaptable and inexplicable works ... He explains it thus simply: «I have always wanted to paint what bothered me and not what I found beautiful».

From this position of a feeling of incomprehension of society would emerge, powerfully and unstoppably, this permanent cry of dissatisfaction that his work would become. It is like a rejection, even, of the whole civilisa-tion that has preceded us, of all that has been sacred and of the dogma imposed. «Everything that is unnatural bothers me, everything that is oppres-síve, everythíng that is false; this repressive and blind context that we have inherited and which has been established over the centuries. All this stinks of death under a futile appearance, apparently well ordered. There are people who adapt very well to this pattern, but I have never been able to. I do not believe in either society or civilisation. There is no beauty in what is false».

And the consequence of this process of disconnection before the setting that did not attract him was predictable: the self-portrait, as a sign of shutting himself off, would be omnipresent ín his work. «I used myself to paint figures in different situations», he justified. And what situations!

A massive personal universe, uncontainable, sometimes harsh, not always pleasant, emerge from a studio of a still unknown author, who lived and worked at night and who closed himself off in an unlit space. And what was taking shape ín those years of deep creative solitude was the most powerful and expressive blue period ever made by any artist in the late-201h century. «Between 1979 and 1982, more or less, I reduced my palette to two or three colours: blue, pink and sometimes grey. It was, if you could call it that, my «ultraviolet» period. I placed red and blue alternately, which I altered with whit . I wanted thus to eliminate the notion of colour, and rebuild an effect of relief using just two shades, warm and cold. This gave a rather muddled appearance to the image, but it was deliberate».

The work that Sandorfi produced in the seventies and eighties, and which forms the main weight of this truly magnificent exhibition which we are proud to present in the MEAM, and which has never been shown in its to-tality, shows an inner lífe as powerful as it is introverted, an intimate cosmos so far from the outside world, that places us before the maximum expres-sion of the protagonism of the I taken to the paroxysm. «I do not speak of physical solitude, but of the solitude of the conception, the solitude of the creation. Art is essentially individual, since art is the science of the feelings, and only the individual is capable of experiencing feelings. A painting can be copied or a style imitated, but you cannot copy a feeling.» It is the over-flowing triumph of the I, galloping runaway through the immensity of a totally personal universe; it is the totally nude artist, alone before the mirror, analysing his more informal positions; it is the explosion of all the most intimate feelings of the human being, without tbe restriction of what is morally correct. What is prohibited transformed into normality, the im-moral converted into the everyday. «I painted a multitude of unsellable paintings, of ferocious, brutal subject matters, which confirmed for some that my painting was a suicide, and that I was deliberately sabotaging my own career».

The Parisian «Galerie Laplace» presented this production prematurely in the <<Musée d, Art Modeme de la Ville de Paris» in 1973, later being the turn of the «Galerie Daniel Gervis» ín 1974, the «Galerie Beaubourg» in 1975, and Munich's «Buchholz Gallerie» in 1976, until the «Galerie Isy Brachot» which, since 1978, has been responsible for his work. Curiously, however, this flirtation with the art market did not have any impression on the nature of his work, where his own persona! drift stood firm. This persona! drift, with this I as the sole unarguable protagonist, would also be reflected, and it could not be any other way, in his sentimental and persona! life. He was incapable of creating a typical family, of having a wife and feeling tempted by the bourgeois concept of the traditional family. «I have never had family spirit, I had a friend who gave me two daughters, and thus we could live eighteen years together. As we lived in a large house with three floors (referring to the house he could rent in 1979 in Saint-Mardé, close to París, opposite the park of Vincennes), I could have a floor to cut myself off and work, and thus it was possible to combine family life and solitude. I sinecerely believe that if we hadn't had a house like that, I wouldn't have put up with a shared lifi ».

And that is how a life ended, conceived as a tale that is written every day, which crumbles and is enjoyed at each moment, which is born and dies around the only real fact, which is the I, without wanting recognitions, without prizes, without social relations, claiming the right to live it in his way, without asking permission for anything. «For me, success consists of being able to live every moment according to my feelings, according to the enthusiasm I have at any moment. Eating when I'm hungry, sleeping when I'm tired, painting when I want to, avoiding obstacles ... Therefore, it is being able to cross the jungle without becoming accustomed, and not climbing the trees to

see where the peaks are. Because in reality, you always end up going down again ... »

Around 1984, Sandorfi made friends with a private collector who would be of great help in his career. He organised exhibitions in Paris ( «Galerie Lavignes-Bastille», 1986), but he also introduced him to the best artistic circles, in the el ICAF of Los Angeles, the «Meissel Gallery» and in «Armory Show» of New York, in London, several years in the PIAC, and ensured that his name was finally heard in the art market. This collector had a very positive influence on the evolution of Sandorfi's work; he ended up abandoning the obsession with the self-portrait and began his series of paintings with female models in the studio. We are in debt to hirn, without doubt, firstly, for

the collection and preservation of twenty years of works from the blue and pink periods and, secondly, for having facilitated the transitíon to the more mature period of Sandorfinian painting. And from here on, and abandoning the relationship with this collector, the big exhibitions continued in his more modern period: The Parisian «Gallerie Prazan-Fitoussi» from 1991, New York's «Jane Kahan Gallery» in 1994, 1997 and 2002, the «Weinstein Gallery» of San Francisco (2003) and, since 2001, and the collaboration with Kalman Maklary ín Budapest.

The reality, however, is that neither the artistic successes, nor the international exhibitions, nor seeing his name recognised amongst the signatures of the time, have been able to change some mental outlines that form his own unmoving personality: «I live with society, but not in it, since I am not associated. To form part of society you have to have been associated with the general activity that guarantees its cohesion». The free spirit continued livíng this persona! freedom, this consciously marginal existence, even when the homages arrived, the signing of catalogues, the luxury books and the major exhibitions.

[/html] [/col] [col different_values="0"] [col tablet="5" desktop="4" wide="4" different_values="0"] [nd_image fid="146" different_values="0" align="center" image_style="wm-original"] [/nd_image] [/col] [html format="ckeditor" different_values="0"]

When he was finally admitted into a Parisian hospital, affected by an acute illness, where he would die on the 26 December 2007, these words of his, so hard but so true, seemed to echo: «I want to ignore society. ln fact, society ignores my painting. It only looks towards the painting that seems like itself, that which is aligned under the direction to which it converges in itself». Now, barely ten years after his death, it is our turn to resuscitate the voice of this great artíst and tel1 hím to his face that society does not ignore his painting, at least we do not ignore his painting, and we will always admire the free spirit, we will always pay homage to the personality of the artist that

transmitted to us, with his art, the most interesting and extraordinary thing a human being can give us, which is his very humanity, apart from the socialconventions and prejudices of the time. And in honour of this humanity we now present in the MEAM the largest exhibition of painting ever compiled and shown to the public, more than 140 works that show the universe of a mind as powerful as it is independent, and which for us, in love with painting and art, is a passionate experience. Moreover, to be faithful to this personal nature of Sandorfi's work, on the third floor of the museum we present a sample of the intimacy of the artist in hís studío: his palette, with the colours he used, his brushes, his wooden easel with the same unfinished painting that remained on it after his death, his slide machines, the same photos of hís models which he took and contemplated, and even the kimonos that he hímself wore when he got clown to work. All of this is clown to the unselfish collaboration of his daughter Ange, who has shown great dedication in order to ensure that this exhibition of her father's work represents the return of Sandorfi to what must be the true destination of his painting, the public at large,

the rest of the community of artists, and sensitive people who wíthout doubt will be able to recognise the work of a brilliant man who created his own world and transmítted it to us for our own enjoyment.

MEAM 2016

[/html] [/col] [/row] [/nd_container] [/col] [/row]