Every day, more than the day before...

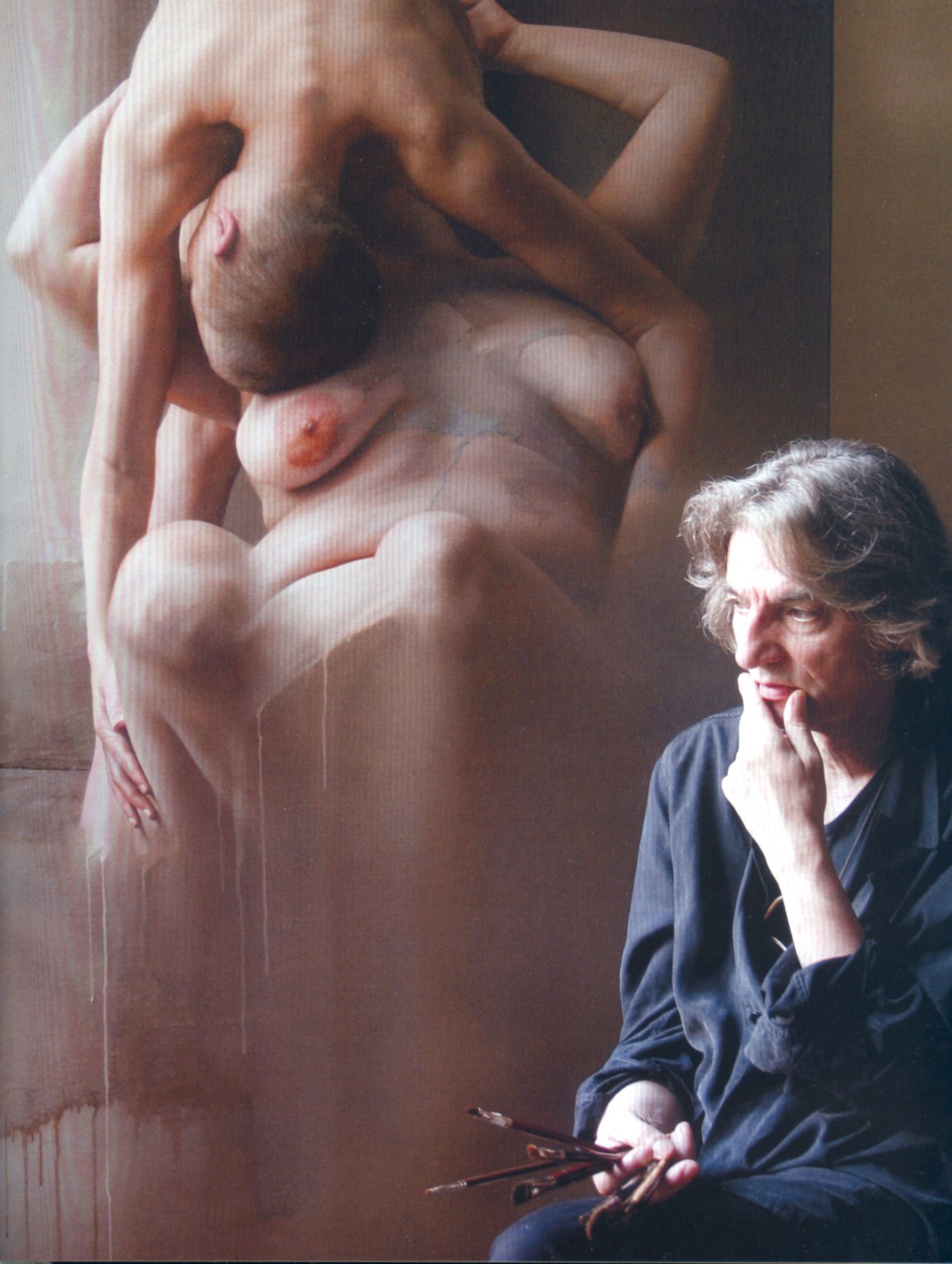

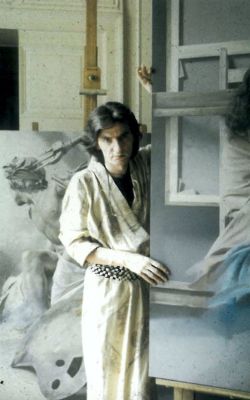

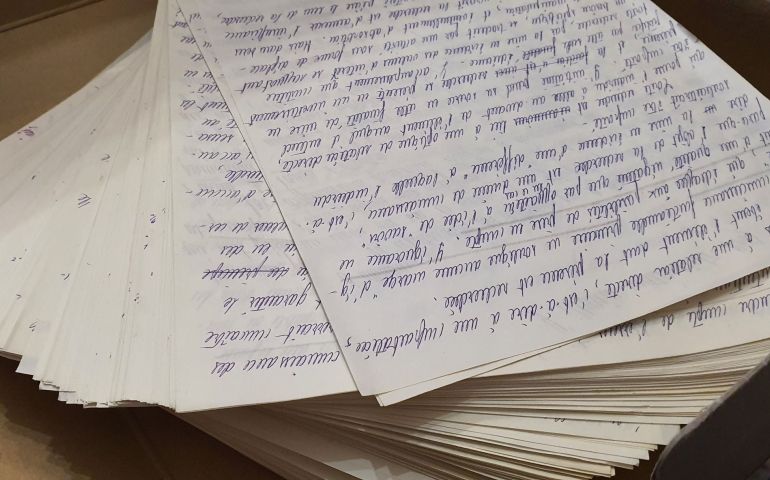

Even though it is true that an artist and their work are clearly inseparable, it might be a mistake to think that Istvan was the reflection of his paintings: perverse, violent, egocentric, asocial. He was everything his work wasn’t. I still regret not having listened to him when he talked to us about his work. He didn’t speak about himself. We hardly knew about what he had to go through when he was young, and the few details came from other members of the family, also sparse, as they nearly always are from victims of tragedies. This is because Istvan was a Hungarian political refugee, who escaped from his country during the anti-communist uprising of 1956. Speaking of his work was speaking of him. But I didn’t listen. The persona fascinated me. I was madly in love with my dad, but I lost a considerable part of his persona. On working on this exhibition, I had to submerge myself in his archives, read some of his writings (he wrote more than 8,000 pages of philosophy about quantum and classical physics), look at, one by one, the tens of thousands of slides that, of course, we have conserved: photos of paintings, holiday snaps and photographic material he used to compose his paintings. Now, with more distance, I can read in his work as a painter as a whole how, unconsciously, he tried to free himself from the influence, positive however, of our mother, his «see you soon» when I lost my virginity, as if he wanted me to belong to him affectively for the last time before «giving me away», his unsatisfying relationship with my sister and his desire for closeness. I was also able to recognise the mixture of contempt and love he felt for his father, and on the contrary, the unconditional purity of his feelings towards his mother. Something important that I have learnt is that it is impossible to interpret a work of art if we do not have the alphabet of its creator. The combination of both gives very literal meaning to each piece, and this exhibition enables me to rediscover my father with great emotion. Istvan was an impulsive painter. He didn’t choose a subject matter, but worked according to his enthusiasm at a given moment. His painting was psychoanalytical, but was not the vehicle of a message. He would not have allowed it since he was a modest person. So modest that he «absorbed» the painful periods of his life to vent his anger in his painting. And although he would never have allowed the killing of anyone that was not himself, it is true that he destroyed the women he loved in his painting, without doubt to avoid any expression that was not artistic of the resentment felt towards them. He was balanced, always calm and incredibly naïve, despite the traumas of his childhood. I love his work. Above all I love the self-portraits. I find them very strong and funny, because they don’t want to say anything. They are simply an excuse for undertaking a technical exercise and of introspection. I have also enjoyed greatly remembering him trying to find a title, a bag of nerves, in front of a finished painting while the transport people were waiting to package it. I laughed a lot on seeing his interviews again: «I get up every day later than the day before». It was always his introduction, and how he explained his lifestyle: he got up when he was no longer tired, ate when he was hungry, panted 14 hours per day, 7 days a week because that was what kept him sane. In fact, he was immature, whimsical and, sometimes, very superficial when on holiday. He lived in a different flat from the rest of the family and stopped working when one of us entered his sanctuary. Sometimes we didn’t see him for a few days. He only washed when he went out because «only dirty people wash» and had developed a very personal elegance collecting old kimonos and ballet shoes: his working clothes.

Oddly, what may seem unstructured for the ordered person was in reality a wise balance: Istvan worked closed off in his world for 10 months of the year and had fun the other two months when my mother, the very beautiful Denise, sent us off far from home during the holidays. We were never exposed to anything inappropriate, and could only guess what he did during those two months, since Istvan was in reality chaste.

[/html] [nd_parallax type="c-bg-parallax c-feature-bg c-semi-circle" content_align="c-content-left" bg_color="dark-2" fid="338" different_values="0"] [/nd_parallax] [html format="full_html" different_values="0"]For us, his family, he preferred working exclusively with dealers for long periods of time. This release from the paperwork of his artistic career, left in these dealers’ hands, and the relative security that this could give him, allowed him to develop a much more polished technique, a process above all encouraged by a patron and friend in the 80s.

Everyone is free to see what they want in Sandorfi’s work as a whole, but personally, I distinguish 3 periods:

The experimental period (until 1975). The works are very avant-garde and violent. The subject matter seems to be unstructured. The liberation period (1980/1987). He almost only painted self-portraits. During this period he lost both his mother and father. The digestion and calming down period, during which he developed a more advanced technique (1998/2007), with the result of a more academic work. Istvan was almost always a UFO inside the art market, except perhaps at the beginning of his career when the Hyperrealist movement was popular. He was lucky to emerge at this time, although he didn’t think he formed part of it. I was able to experience the ups and downs of his career, which made him suffer greatly, since attacking the finished product of his introspection was, of course, attacking what he was. And this is precisely what the professionals of the art world are often unable to understand. Moreover, do they have the tools for it? He told us that, one day, he gave a talk in the Fine art school, if I remember well. It was one of the only good memories he had of his career as an artist outside his studio. He had loved the openness and sincere curiosity of the «not yet corrupted» students. He would have been very proud of knowing he has passed onto the side of popular culture. Unfortunately, Istvan is no longer the art market’s cup of tea, but he is still a cult artist, a «rock star» of painting as his last dealer often said: he is a source of inspiration for fashion, photography, music and body art.

He said to us, «I love you today more than yesterday, but much less tan tomorrow»

We miss him every day, more than the day before…

[/html] [/col] [/row]