INTERVIEW WITH ISTVAN SANDORFI (1976) ABOUT THE WAY OF PAINTING

Journalist: Istvan, you arrived in France in 1958, aged 10, didn't you?

Istvan: Yes, in 58, aged 10.

J:Why?

I: We are Hungarian refugees. We lived two years in Germany, and then we came to France. Since then I have always lived in France. I did all my studying here.

J: Did you also study Fine Art in France?

I: Study Fine Art ... perhaps there is a nuance here. I «enrolled» ín the Fin e Art School for 6 years. I also went to the Decorative Art School. But that was for family reasons.

J: And you didn't actually attend class?

I: I didn't go to classes ... although I have a qualification in Fine Art, which is odd. I think it is the only school ín France where you can get a qualification without going to class, which is perhaps specific to Fine Art teaching but it does have its advantages. It allowed me to give my father a small gíft: a quali-fication that is at the bottom of his draw.

J: Does it bother you if I say your painting makes me feel bad, like that of Bacon and Dado?

I: No, though it doesn't bother me. This way of disconcertíng people for their morbid personality, for the image of their death and the questioning of their structured life just like in current times and for everyone ...

Perhaps the fact, not of being Hungarian, but of having expericnced events that not everyone has the privilege of withstanding has given me a type of dimension of myself, of life.

Of course, these events have disturbed me and have allowed me to see things more lucidly, more openly. My first drawing is from that period. They were Russian soldiers killed by revolutionaries. A boy of 8 who draws machine guns and blood is something ... not strange, but unusual.

" I make a choice from hundreds of slides I have taken of very diverse materials."

[/html] [/nd_parallax] [html format="ckeditor" different_values="0"]J: (Istvan begins working -Istvan, before the digital age, projected several subjects that he included in the composition of the painting in progress on a blank canvas to get an idea of the possible result).

I: To establish the choice of painting, I make a choice from hundreds of slides I have taken of very diverse materials. They all have a similar theme, some slightly different from others due to their plastic interpretation, but they have a similar theme. It is quite complicated to produce the final composition, fo-cusing it, making it plastically rather satisfactory.

I project the slide onto the canvas. I make the outline of the focus, and then I don't project the slide on the canvas any more, but on the screen that is per-manently on. I use the image as a model as if I had a live model there.

J: Some art purists would say to you that the elimination of the drawing may represent a danger. Don't you take away a little of the skeleton, the structure of the painting?

I: I have to work with the technical means I have at my disposition. I deliber-ately choose a more direct path, which is not always the easiest, but wlüch eliminates any totally useless technique.

J: Do you think that drawing today is something useless?

I: I don't see why I should play around with a sketch on the canvas when I have an immediat focus from a projection. I simply draw the outline. It is simply eliminating superfluous work and which I don't have to do. ln any case, that is not what matters. The fact of projecting the image that I will use onto the canvas corresponds to a living model. The problem is solved this way ... the problem of the model and the painting. There is no innovation.

J: Don't you see this as a bit of an easy way out? It is the reproach made to all painters, above all American painters, the hyperrealists who use these meth-ods.

I: It is not exactly the same method because I don't do a photographic paint-ing. The photo doesn't inspire me, I don't copy the photo, I don't use photo-graphic tricks. Photography is a means, a support, a documentation, that en-ables me to have a much bigger field of action. I've been painting from photos for almost three years now but when I didn't do it, as I had problems with realist details, which I have always had, it was obligatory to have a rnodel... A packet of cigarettes, anything ... which was painted before me, with the light I had, which reduced the subject matter to some very limited examples. And it was a model, in general myself, since I was the only one always available to myself, which from the thematic viewpoint, was very limiting. However, now I can paint anything. Everything that comes to mind: hands, cars, babies. How can you make a baby pose?

" Drawing disturbs me, it can take me away from the technical sacrifices that we must make to prepare the oil painting in all its meaning."

[/html] [/nd_parallax] [html format="ckeditor" font="font-second" different_values="0"]J: It's very interesting the distinction you make between a painting that is very much inspired by photography, that is the American or European hyperreal-ists, and yours.

Is the photo, for you, a first means, a support?

I: It is not a means. It is not a support. It is a help, a simple documentation. If one day, I find myself without the possibility of projection, without pho-tos, if someone steals my whole collection of slides and if I can no longer paint without a photo, I will still produce paintings. I don't paint systemat-ically from photos. ln fact, the photo over each canvas is no more than documentation. I do them from a combination of very diverse photos, but no photo represents the painting as such. Moreover, not all the backgrounds are photos. I invent them. I place them after, to give a focus, to create an atmosphere.

J: Do you know how to draw?

I: Above all, I am an illustrator. I spent all my youth drawing. I love drawing. But it is something I have eliminated since one day I realised that with painting, the colour, volume, relief, the truth that my painting can offer, there were much more direct possibilities. Drawing disturbs me, it can take me away from the technical sacrifices that we must make to prepare the oil painting in all its meaning. Precisely, I have eliminated the drawing to be able to ...

J: To devote yourself entirely to oil painting?

I: But I don't regret anything ever.

J: To simplify?

I: To simplify. To free my mind. ln order not to scatter my mind.

J: Many artists paint during the day, as tradition would have it, usually in stu-dios with natural light. In your case it's just the opposite, you paint at night, obviously with electric light. Is there a particular reason for this?

I: At night we don't have, at least in my case, I am not in the same state of mind as I am during the day. We live on a different scale. Time almost reduces to its smallest image. We completely forget it. We area different species. It has a different conception of life.

J: Unarguably, more lunar than solar.

I: That's right, I don't like the sun. Nor the day. The day blinds me. At dawn, when I go out for a while before going to sleep, I am perturbed, as if I was drugged by the daytime.

J: You sleep during the day, then?

I: I sleep during the day.

J: Don't you think there is a danger if we cut ourselves off from the outside world? Seeing as you cut yourself off on purpose ....

I: No, I'm not a savage in any way. I am solitary, but because I need to be alone.

J: To focus?

I: I only exist individually and totally when I am alone, but I need society. I have friends, I am very simple in this way.

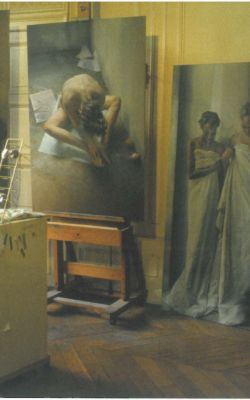

J: (watching hím paint) Don't you mix the colours on the palette?

I: I míx in any way on the palette. I take colours which, for me, are the right ones, and look for the exact tone on the canvas. Sometimes I make mistakes. That's why sometimes there is a fairly thick layer. However, ít is not the thick-ness that matters: what matters is how it is spread. It is always important to spread your colours with a dry brush to obtain a totally smooth material.

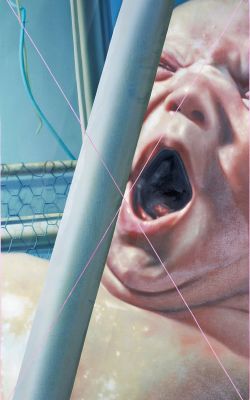

(The images show paintings of babies)

I: The image of the child and the baby in particular began to ha unt me when I had one, when my wife became pregnant. Before that, I hadn't thought about representing the physical image of a child, of a baby that that always seemed ridiculous to me. The image of the good baby, from the type of fami-ly that was totally unknown to me. I paint babies as if I were paínting a still life.

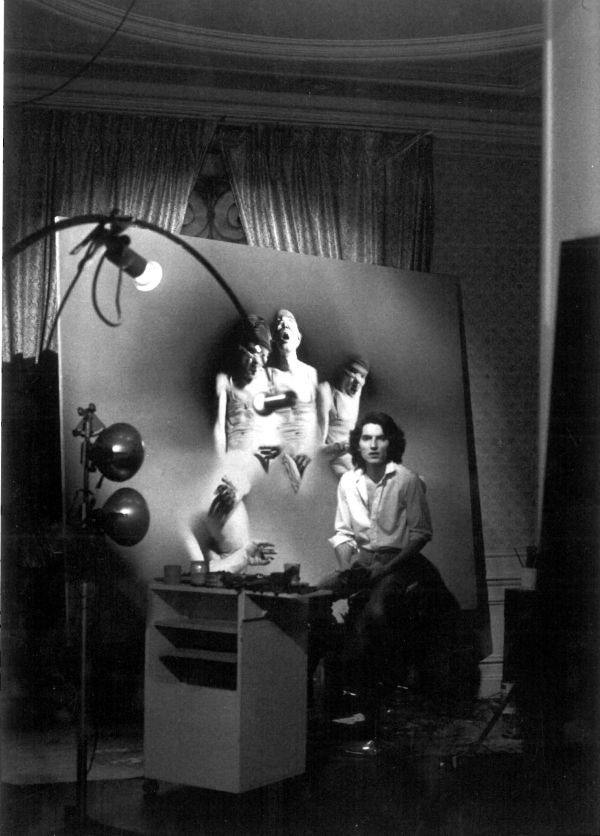

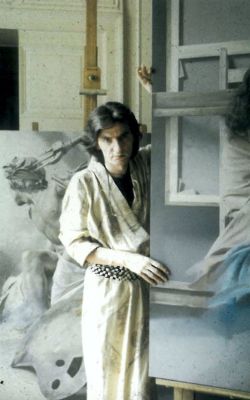

J: There is something rather stunning, and that is the abundance of self-por-traits. I think we could talk about this peculiarity.

I: Initially, painting self-portraits was a type of saving for me. It was the only model always available and at that time I didn't paint from photos or from slides. Gradually, I systematically chose my own image for connections I found interesting, between the painter, the choice of his image, the painting, the relationships that this could create, this space of there and back, ln my case, perhaps there had been, not really a question of narcissism, but rather a question of masochism. I've painted myself with cuts on my face, with spots, with eczema.

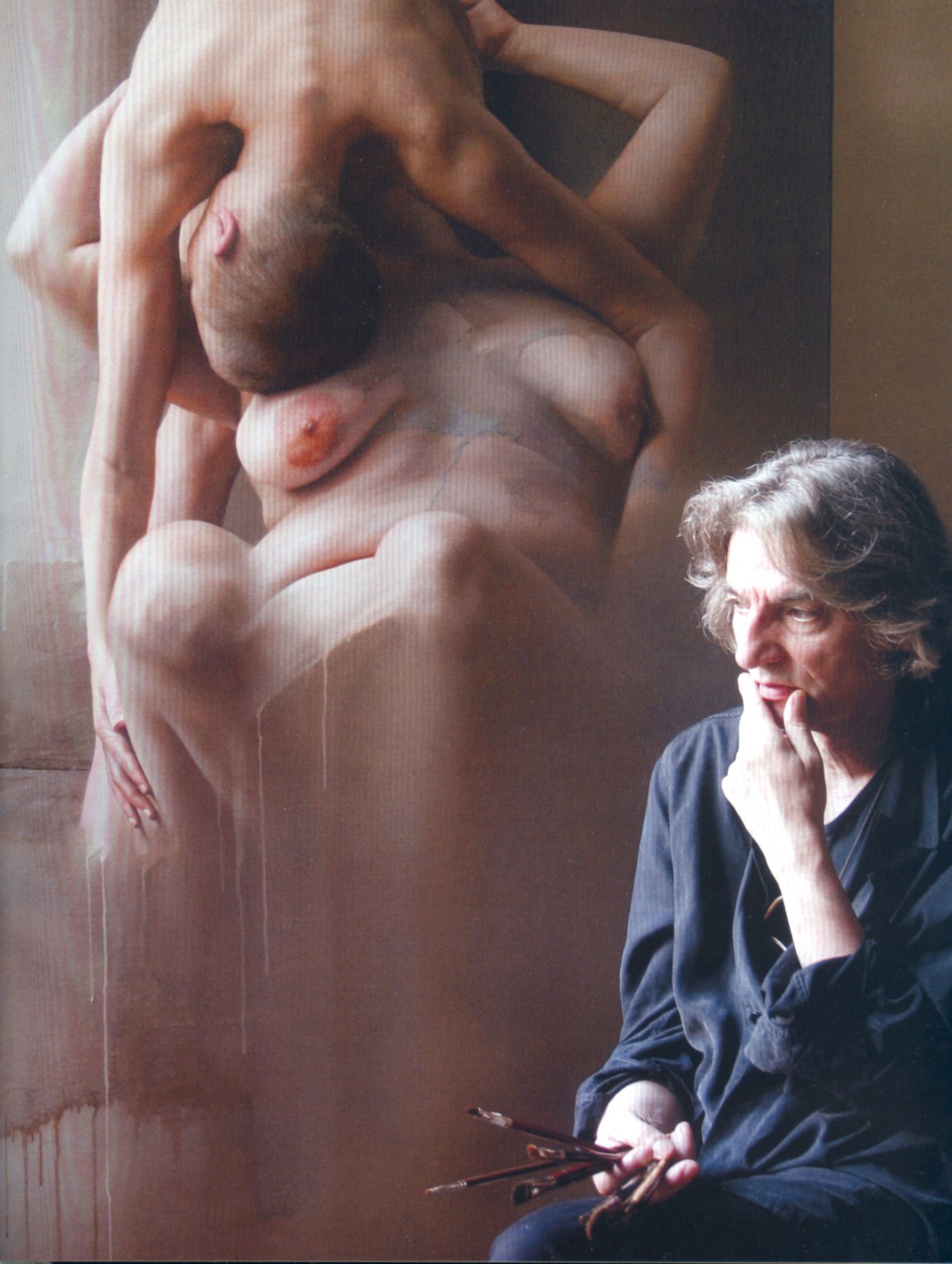

J: Perhaps there is for me ... I don't know how others see it, but the fact of representing human flesh, above all human skin, is without doubt one of the elements that bothers me. Skin, flesh, is an argument you use a lot. You are quite a carnal painter. There is always flesh.

I: There is a physical sensuality.

J: Do you place this at the level of sensuality?

I: ln fact, the problem is the following for me: I believe that between sensitiv-ity as such, that is to say feeling, intellectualised or not, and sentimentality, sensuality, there is a very fine nuance. We can use a feeling, a sensuality, a fairly primary sensation, almost instinctive which is that of the flesh, through a more less complex process, to the exhaustion of the emotion, to arrive there-fore at sensitivity.

J: Why do these hands always appear? We don't know what they are going to pick up. What they are reaching out to. Is it an obsession? A personal fantasy?

I: It is a choice that satisfies me because it allows me all the plastic variations without falling into the trap of the easy anecdote, of the symbol, of the imme-diately smoothing, of the image tied to a story by a vehicle, a well-defined context. It therefore allows me, plastically speaking, all the variations of trans-parency, of chromatic uncertainty, of variety of rhythm, yet conserving a typ-ically human spirit, which is very clearly related to an everyday experience without ever being related to a well-defined symbol, with a story, an anecdote. It is present in each of us and conserves a very lively nature.

J: When we see all these faces, these bodies and, at times, these objects ín de-composition, those glances often hidden by glasses even in the children, when we see these hands, stretched out, handcuffed, often tied, we can ask our-selves ... there is an immense discomfort. I will say that word again since for me you are, and will always be, and this is without doubt one of your main qualities, a painter of discomfort, or of a certain discomfort. I would like to ask you: what do you hate most, others or yourself?

I: Nobody. ln fact, the act of painting, the creative act is an act of love and generosity. I don't hate anyone, quite the opposite. And even less myseff It is not hate. It is not about feeling, it is not about this category of feeling. It is about ... how can I say it?

J: When you paint, are you giving or taking?

I: ln fact, l think I give more than l take. I get the impression that I take from myself and that I myself give. It is an act of sacrifice and total disappearance. Of course, ifit is taken to the extreme. ln fact, the act of creating, of transmit-ting, of creating a guinea pig, because in the end l am my own guinea pig, with a small «g», it is an act of generosity. Of generosity to «x», that is, it is not al-ways personalised. And that is essential. I think that someone who shows a feeling of rejection towards others, towards themselves, cannot transmit the social act that is embarking on a painting.

[/html] [/nd_container] [/col] [/row]